Lesson 2 – What is “good enough” for you?

In the last lesson, I briefly reviewed what the fundamentals are, why they are important, and how we can strengthen them.

One of the things I discussed in that class was that because foundations are inevitable, the quality of your life depends more on your weakest foundations than your strongest foundations. Having a lot of money doesn’t mean much if your relationships or health aren’t good. Likewise, even if you have a great career and family, you can still feel terrible if you don’t get enough sleep.

It follows from this that, for the foundation, Mediocrity is more important than proficiency. While your career or hobby may benefit from specialization, “good enough” is more important than great for your foundation.

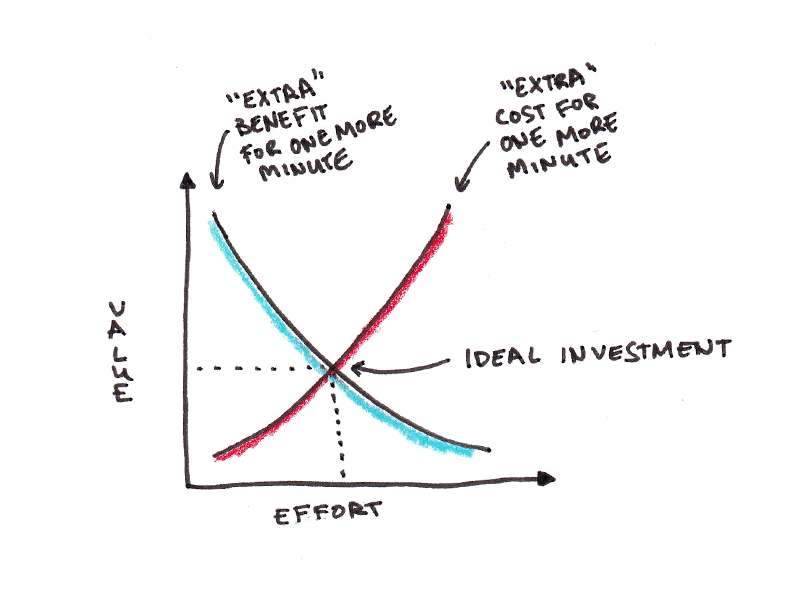

The benefits of investing more effort in the fundamentals are not linear. Instead, they form a classic diminishing returns curve:

As you can see in the chart, the benefits are greatest when going from zero to good enough compared to going from good to amazing.

For some basis, we have good data on the shape of that curve. One of the benefits of regular exercise is that it reduces the chance of premature death. Going from zero to 75 minutes of exercise per week (half the standard recommendation of 150 minutes) reduces this chance by 20%. By comparison, exercising for 150 to 300 minutes per week would only result in an additional 10% reduction (for a total reduction of 30%), while exercising more than five times the standard amount (i.e. 12.5 hours per week, or nearly two hours per day) would have essentially no additional benefit.

in other words, If you care about your health, doing “some” exercise relatively consistently is far more important than beating your personal best in the gym.

But another thing you’ll notice is that the shape of the curve is smooth. Meeting the guidelines is not the “right” amount. If you want, you can do about three times the recommended amount and still see added benefits. Alternatively, you can take the opposite approach and only do half of what is recommended, but you will still get 2/3 of the benefits of someone who follows the guidelines closely.1

Given this, how much is actually “good enough”?

Feel your “good enough”

There are trade-offs, so figuring out what’s “good enough” for you is an important part of the good life puzzle.

For starters, there’s one obvious fact: Different people have different costs for different foundations. An able-bodied twenty-year-old might have no problem exercising for two hours a day, but a busy working parent might struggle to find fifteen minutes.

Secondly, even within a person’s lifetime, We need to consider the trade-offs between different bases. If exercise means waking up early and losing sleep, should you exercise more? Should you spend your evening reading or socializing with friends? Should you save money or spend it on a family vacation?

If we were the mathematically inclined robots that economists imagine us to be, we would solve this problem simply by continuing to invest more in the practice until the incremental benefit of the behavior equals its incremental cost. So, start with zero exercise and keep adding five minutes to your day until the extra five minutes benefits you less than it costs you.

In practice, however, the actual shape of this curve is not always known. Even for well-studied subjects such as fitness, where we have good mortality data, it is difficult to interpret subjective benefits such as improved mood and energy. Even if we do understand them, the costs themselves are subjective—how much do you value five more minutes of sleep or five more minutes of time with your kids?

Instead, we have to weigh these trade-offs more based on feelings rather than numbers. For you, the “good enough” threshold for basics is when you feel that any more basics aren’t worth it compared to what you have to give up elsewhere in your life.

While it doesn’t feel like things are accurate, it’s not impossible. There are even some good arguments suggesting that the algorithms run by these imaginary, mathematically inclined robots are actually used by parts of the brain when making choices.2

Instead, the problem we have is not subjectivity but that the costs are not constant.

Improve your “good enough”

Exercise is a perfect example. While many people are concerned about not having enough time to exercise, time alone is not a good explanation for why we don’t move enough. As many time-use surveys show, we spend enough time on television, podcasts, or other activities that even very busy people can usually find thirty minutes a day.

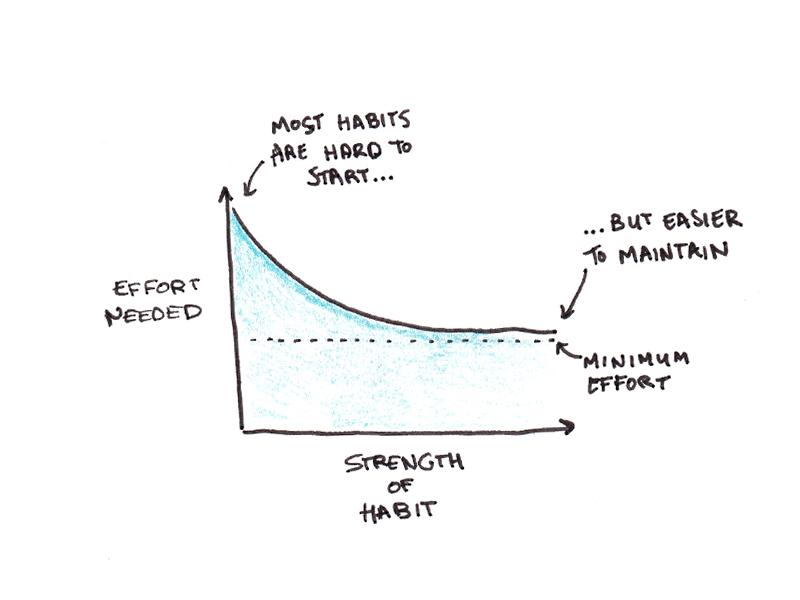

Instead, the reason we don’t exercise is simpler: Exercise is difficult and unpleasant, especially when you’re out of shape. In other words, it’s not that time keeps us from doing it, it’s that exercise seems to require so much willpower and energy. We would rather relax at the end of a tiring day.

However, if you exercise more, it becomes more enjoyable. Your body is in better shape, so you feel better about exercising. You allocate time to it regularly, so there are fewer temporary difficulties in scheduling. You can even participate in a sport or social event to make your workout more than just moving your muscles.

I think this explains why, despite the fact that weaker foundations have a greater impact on our lives, we often get bogged down in making small adjustments to our strongest foundations. As we gain more confidence and experience, the cost of further investments decreases, so we are more inclined to make these easier investments, even if they provide smaller and smaller returns.

This is also an argument for subjecting yourself to mandatory maintenance on all foundations, even those you normally avoid. Because if you can lower their ongoing costs, you may find that you can get to a higher level without a lot of extra pain and effort.

What is “good enough” for you?

I’m curious how you draw the line of “good enough” in your own life. What is your foundation for maintaining high standards over time? What is the minimum requirement that you find difficult to meet? Please comment below and let me know!

_ _ _

On Friday, I will announce the next Basics course and outline the twelve-month course, including my recommendations for getting the most out of each Basics course.

footnote

- Interestingly, when you ask people if they meet the recommended guidelines, most adults say they do. However, when activity was actually tracked, less than 10% met the guidelines. We often deceive ourselves about how strong our foundation actually is.

- Of course, our neural circuits are not wired to easily consider long-term interests, which is why those interests that are primarily in the future are often overlooked.