How to make hard work easy

Lately, I’ve been writing about improving my energy. Recent articles include why we should manage energy rather than time, the saga of ego-depletion research, and the paradoxical relationship between stress and energy.

Today I want to talk about effort. Why do some tasks feel harder than others? How can we make the hard work we need to do easier?

What makes things difficult?

Why does solving a math problem in your head feel strenuous, but scrolling on your phone or playing a video game doesn’t?

A naive answer might be that some tasks are more laborious because they use more of our brains. Casually, we sometimes talk about “turning off our brains” when we are too exhausted to perform mental work.

This is an intuitive idea, but ultimately wrong.

Just opening your eyes creates a surge of neural activity in the part of the brain that processes vision. So if effort simply amounts to using our brains, then watching a video should be harder than solving a math problem with your eyes closed.

A better answer is no all Brain activity feels strenuous, but brain activity associated with deliberate control often does. The parts of the brain most clearly associated with subjective feelings of effort are those associated with working memory and executive control.

But here we also encounter some difficulties. Playing video games isn’t as strenuous as solving math puzzles in your head, but both require full concentration. In contrast, staring at a blank wall requires no working memory but is very difficult to maintain for more than a few minutes.

The best explanation I’ve heard for this is that effort is a feeling of opportunity cost. Basically, our working memory is limited and required for most tasks, so we must use these resources wisely. When we engage in low-return activities that monopolize these limited resources, we experience it as effort.

This helps explain why video games feel effortless despite being cognitively demanding, and why boring tasks, like staring at a wall, feel effortful. Video games are designed with a variety of intrinsic and immediate rewards that keep us engaged. Staring at a blank wall is hard when we could be doing something more valuable with our brains.

effort and fatigue

Therefore, motivation, specifically the immediate reward predicted by dopamine networks in our brains, plays a crucial role in the perception of effort. If we are doing an activity that continually rewards us in the here and now, we will find it less strenuous.

In contrast, if other activities (including daydreaming) provide better immediate rewards, more effort will be required to continue completing the task.

I’ve shared this opportunity cost theory of effort before. I believe this is true, but I think when I wrote that article I missed the core of the truth buried in the now somewhat tainted ego-depletion research: namely, that our capacity for effort is not constant.

When we are well-rested, energetic, and optimistic, we have a higher ability to perform strenuous activities. Conversely, if we are exhausted, sleepy, or depressed, even moderately intense activities can feel incredibly difficult.

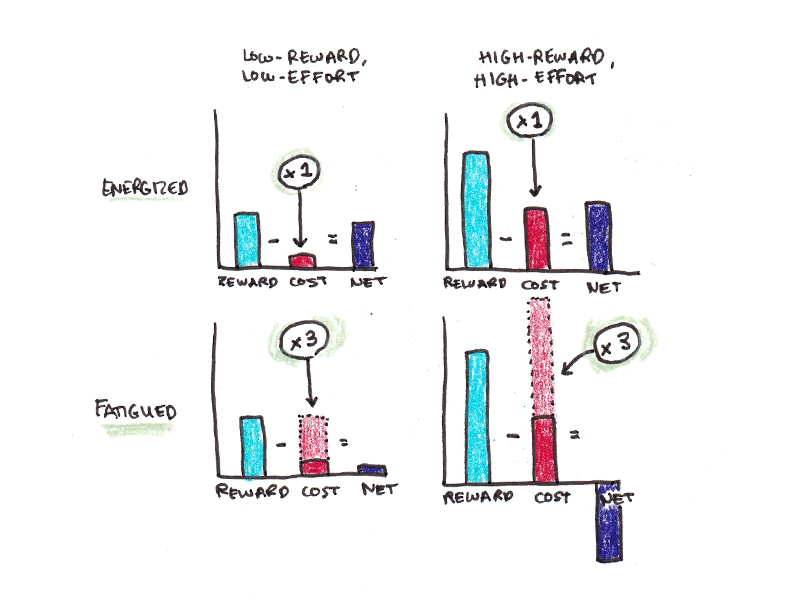

Consider two different activities. One is low effort and has low long-term rewards (e.g. cell phone scrolling). The other is high effort with high long-term rewards (such as studying for an important exam). What we choose to do will depend in part on our energy levels – it’s not impossible to learn when we’re low on energy, but we’re much less likely to choose high-effort/high-long-term reward tasks.1

This helps reconcile the “energy as resource” and “energy as power” perspectives. When we are depleted of energy, motivation is tilted so that the effortful activity must bring greater rewards in order for us to take action.

Three ways to make hard work easier

All of this goes to show that there are some levers we can pull to make the hard work we need to do easier:

- We can make tasks less strenuous.

- We can make the task more valuable in the long run.

- We can increase our baseline energy to make the effort itself easier.

Let’s look at each:

1. Find flow: Make tasks less strenuous

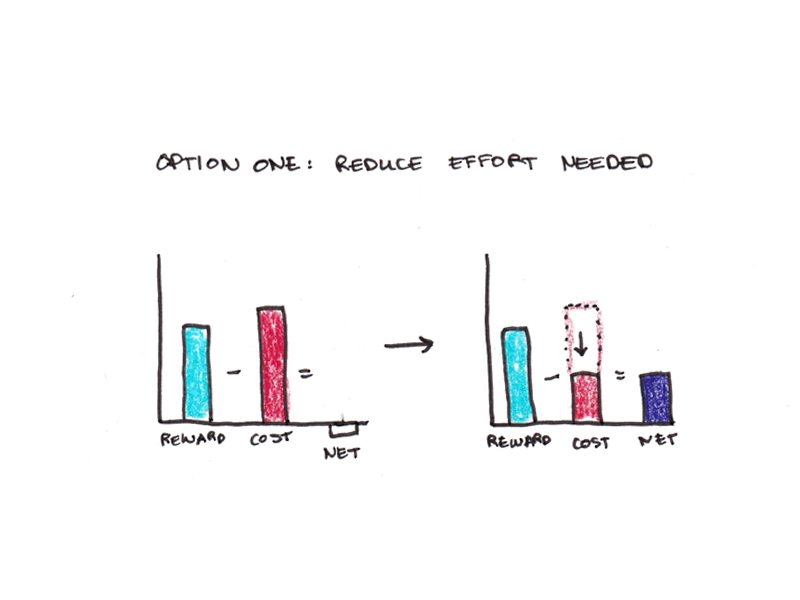

Since effort is a perception of the opportunity cost of using general executive control capabilities, there are several ways to directly reduce task effort.

We can make difficult tasks easier. This can be accomplished by lowering our standards (e.g., targeting bad first drafts or not allowing review during brainstorming). This can be accomplished by turning to a “meta” task that first seeks to understand the source of our difficulties (e.g., journaling, rubber duck debugging, or the Feynman technique). It can also be accomplished through learning and experience, which makes initially laborious tasks increasingly automatic.

We can make boring tasks more engaging. We can do this by raising the bar to make tasks more challenging, adding constraints and complexity, or turning them into a game to increase their intrinsic rewards.

Finally, we can adjust the types of alternative tasks we engage in. If we reduce the temptations and distractions nearby, less effort is required to complete the exact same task. Go to the library to study instead of staying home and watching TV, and be wary of the abundance of shallow and simplistic media that drains our motivation to do more difficult things.

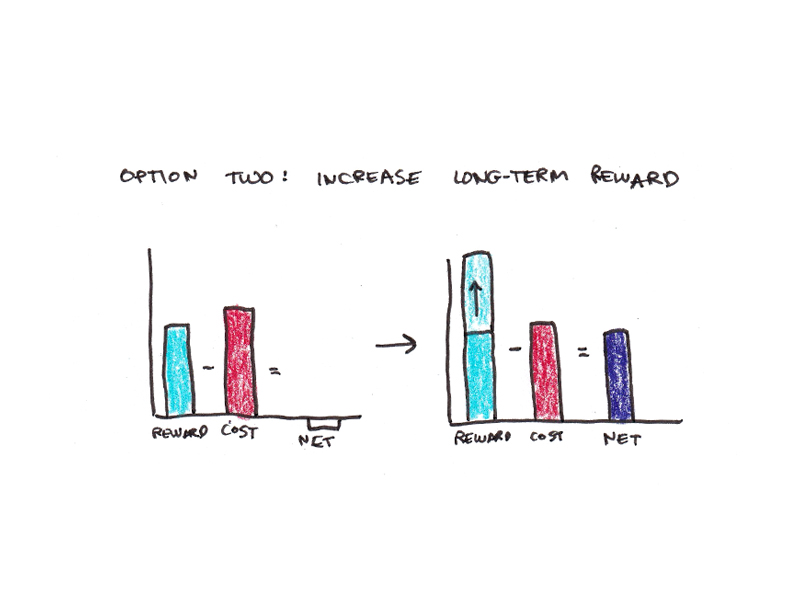

2. Create motivation: Make tasks more deeply motivating

Alternatively, we can increase motivation to do difficult things by choosing more inspiring projects and goals rather than trying to reduce the workload. When you’re doing something that feels very meaningful and important, it’s much easier to push forward with a temporary effort than when it feels pointless.

Finding more motivating projects to work on is a profound topic in itself. Part of this skill comes from exposure. Some thoughts are naturally good, while other thoughts are bad. So if we don’t have a large pool of ideas to implement, we naturally lack motivation.

However, we all know that simply having a good idea is not enough to inspire motivation. We need to have confidence that we can achieve this goal. This belief is built through positive experiences. We need a worldview that values the goals we pursue. Perhaps most importantly, we need to be in an environment that truly rewards our efforts.

Creating more purpose and meaning doesn’t solve the problem of effort—the most motivated people in the world still work hard—but it makes it easier to overcome apathy and stagnation. Even heroic efforts are likely to persist if long-term motivation is evident.

3. Replenish energy: make hard work easier

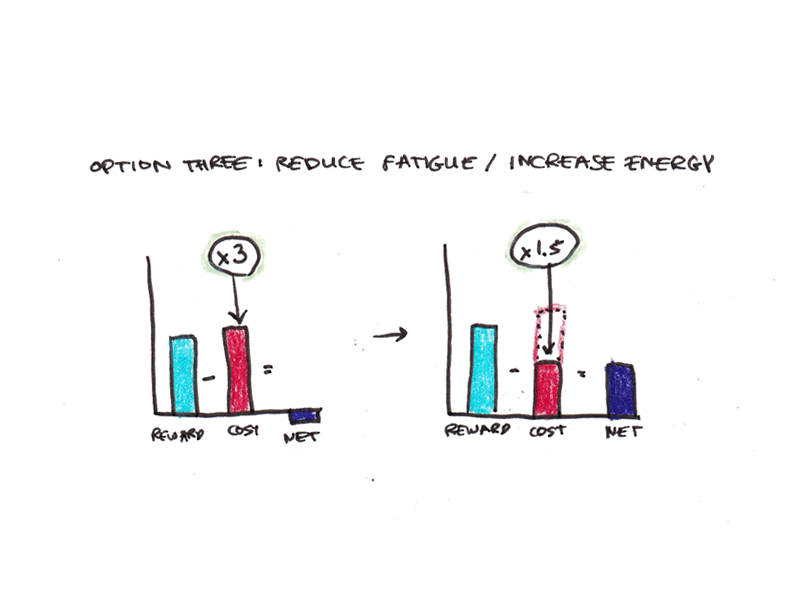

Finally, we can work to cultivate bottom-line energy that makes efforts easier to sustain and inclines us to do more difficult things.

Some of it is biological. As I discussed in my article on stress, brief periods of stress can energize us, improve our focus, and motivate us to take physical action. However, chronic stress drains our energy because it compromises our body’s investment in repair and recovery, ultimately leaving us exhausted.

This means it’s important to develop good lifestyle habits (such as regular exercise, good sleep, and a good diet) as well as engage in stress management practices such as self-reflection and building strong relationships. While we have limited control over our health—many of us suffer from illnesses or conditions that are no fault of ours—taking control of our health can have a huge impact on our ability to work hard.

This is perhaps the biggest benefit of my recent foundation project. By improving my sleep, eating, and fitness habits, the work I needed to do to maintain my business and take care of my family felt much easier, although the effort required to complete these tasks and my motivation to complete them did not change.

_ _ _

This article is just an introduction. In fact, all three steps: making work easier and finding a flow, making it more meaningful and increasing your motivation, and cultivating the fundamental energy that powers you are all great topics to discuss.

To help achieve this, I’m launching a new course, Everyday Energy, which synthesizes research findings into a practical roadmap for those who want to improve their energy.

In the meantime, I’d like to explore some of these topics in more depth as I continue this series of articles. Next I want to see how our time is spent no Work affects our energy levels and try to answer the question whether it is more restorative to relax deeply or engage in more active activities in your free time.

footnote

- One confusion I have is that if effort is a relatively rewarding feeling, how can an activity be both effortful and rewarding? My best understanding now is that the neural circuits that produce feelings of effort are more sensitive to immediate rewards as part of an activity and less responsive to long-term rewards. This suggests that when we are tired, we become more sensitive to delays (more impulsive) and subjectively we perceive short- and long-term rewards differently.