The relaxation paradox: Why distractions don’t always restore your energy

The work we do affects our energy. Working nonstop in a toxic environment with a lack of control puts us directly on the path to burnout.

but what we did back Work is also important. If we recover adequately after work, we can maintain high energy even under difficult conditions.

Today, continuing my ongoing series on energy management, I want to take a look at our time outside of work: what we do during our breaks, and how our leisure choices determine how much energy we have at work.

Relax or engage?

One question is, are activities like lying on the couch, scrolling through your phone, or watching TV more restorative than more complex activities like hobbies, sports, or personal projects?

However, before we answer this question, we need to understand what it means to “restore” energy. Researchers use two different dimensions to describe what I call “energy”: fatigue and vitality.

Fatigue is a feeling of exhaustion, exhaustion, and exhaustion. From this perspective, the more we work without recovery, the more fatigue we experience. This feeling is amplified when our jobs are demanding, strenuous, or stressful.

Vitality, in contrast, is a feeling of being inspired, engaged, and driven. When our psychological needs for autonomy, control, and relatedness are met, we feel energized, so our actions feel voluntary and meaningful.

Although there is legitimate tension between the two ideas (fatigue is often associated with low energy and vice versa), they are conceptually different. We may be energized but also fatigued, as in the final sprint to finish a race. We may also lack energy and be tired, like not wanting to get out of bed and do chores on a lazy Sunday.

Energy recovery can affect our fatigue, energy, or both, depending on what kind of recovery experience we are having. Researchers studying this question classify these experiences into four types:

- separation. Being able to escape the stress and stress of work at the end of the day.

- relaxation. Calming, stress-reducing activities.

- proficient. Address challenges and pursuits that are personally meaningful.

- control. The ability to choose how to use our free time.

Please remember that these experience Not a one-on-one casual match Activity. Instead, think of them as different components of a different recovery experience. For example, we might gain detachment and control, but not mastery, from watching a movie; or we might gain detachment, mastery, and control, but not relaxation, from playing tennis.

In a meta-analysis, the researchers found that detachment and relaxation were more strongly associated with reduced fatigue, while mastery and control were more strongly associated with increased vitality.

This suggests that feelings of exhaustion benefit more from detachment and relaxation, whereas feelings of low motivation and drive benefit more from satisfying our psychological needs for competence and autonomy.

How to recharge during breaks

This leaves us with the question of which leisure activities actually produce detachment, relaxation, mastery, or mastery.

Some solid findings emerged here:

Unsurprisingly, doing chores at home doesn’t do much to restore energy. So-called “high responsibility” activities may not be part of our jobs, but they still feel like work and don’t help restore our energy.

Importantly, our interpretation of these activities is less important than their objective characteristics. For example, caring for children can be a joy or a burden, and therefore rejuvenating or exhausting, depending on whether we enjoy spending time with our children or view it as an obligation. Likewise, many household chores, such as gardening, carpentry, or home organization, can become hobbies.

The key difference between “active leisure” and “housework” is whether the pursuit is intrinsically motivated. This, in turn, depends on whether the pursuit is voluntary, involves positive connections with other people, or can provide experiences of competence and mastery.

Another finding from the same literature is that while “recovery experiences” are important, they pale in comparison to the impact of sleep. Good sleep is 2-3 times more effective than restorative experiences, suggesting that while staying up late to watch an extra episode of TV may help us relax, its benefits are diminished by lack of sleep.

Additionally, while relaxing through activities such as watching TV or using digital devices can help reduce fatigue, they are unlikely to help increase energy because we generally do not find them particularly satisfying or meaningful. This suggests that if we can spend our free time in a way that meets our deeper needs, we will be more successful at restoring our energy.

Finally, physical activity has a huge impact on energy levels. This is attributed to some of the powerful physiological effects of exercise as well as the psychological benefits of the recovery experience. Mentally engaging but primarily sedentary leisure activities, such as painting or baking, are often better than completely passive leisure activities. But it would be more effective to include at least some physical activity in our downtime.

exhaustion cycle

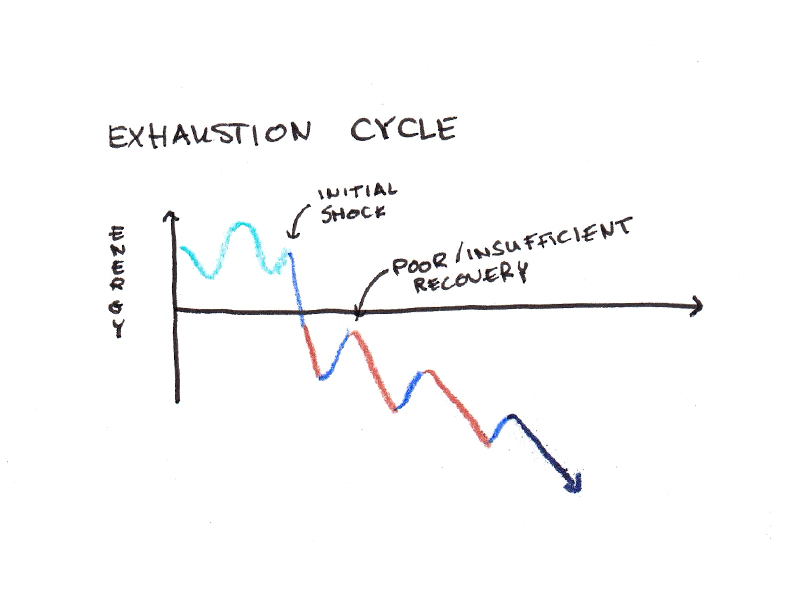

If you’ve been struggling with low energy, you may have noticed a problem: all the “better” leisure activities tend to be more strenuous!

This creates a paradox: When we don’t have energy, we turn to low-effort leisure activities. But because these activities don’t really satisfy our deeper psychological needs, they aren’t particularly uplifting.

This often creates a double whammy: we become overwhelmed or stressed by pressing work demands. As work pressure increases, recovery becomes even more important. However, because we have less time and energy, we reduce active leisure, physical activity, social interaction with friends, and the additional stress makes our sleep quality worse. As a result, short-term stressors can easily turn into a cycle of exhaustion, leading to burnout.

This is unfortunate news because it shows how easily our energy levels can fall into a downward spiral.

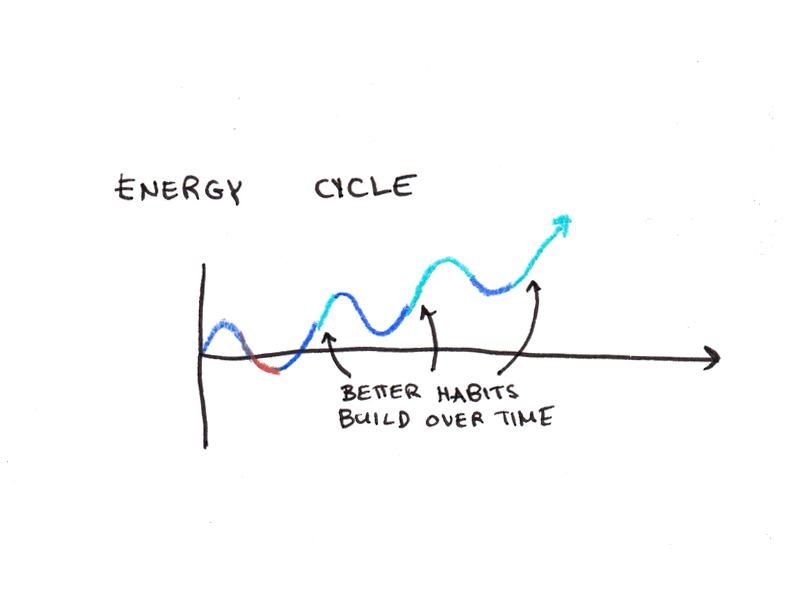

But another way of looking at it is that the spiral of energy also runs in reverse. Just as a sudden job wave can cause a cascading decline, small positive changes can intensify. Small actions to restore energy—increasing small amounts of physical activity, dedicating a short period of time to fulfilling psychological needs rather than just doomscrolling, making a little extra effort to go to bed earlier—allow us to make a larger investment in energy and thus reap a larger return.

We can create a cycle of enthusiasm and energy rather than a cycle of exhaustion. The key is to take the first step.

How do you fully recharge after get off work? What are the barriers that prevent you from feeling energized? Share your thoughts in the comments!