Manage your energy, not your time

Every now and then I get an email from a student preparing for the college entrance exam. They’ve mapped out a timeline for how they’ll study and end their emails with a nervous “What do you think?”

My response is always disappointing: “Well, it depends…”

There were some obvious reasons: I didn’t know the exam. I don’t know their level of ability. I don’t know what they already know.

But there’s a deeper reason for my ambivalence: I don’t know if they’ll be able to stick to the timetable they’ve set for themselves.

Making a schedule is easy. Sticking with it—especially when the work involved is cognitively demanding—is incredibly difficult.

The myth of time management

A few years ago I started writing an in-depth research paper on the history of productivity, similar to my other complete guides. I eventually abandoned the project and started writing my second book, but I still remember reading many 19th-century books on the emerging science of productivity.

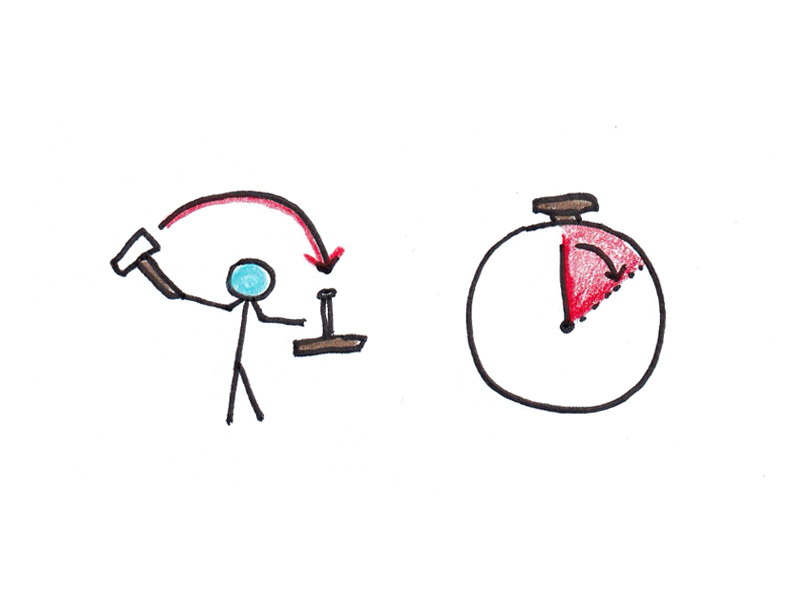

Early thinking about productivity centered on factory work. Time management was understood in terms of seconds rather than hours, and theorists like Frederick Winslow Taylor actually timed workers’ movements with stopwatches in their hands in an attempt to squeeze greater efficiency from the workers who happened to be under his gaze.

While “work” increasingly shifts from making parts to manipulating symbols, the focus on time continues. Management guru Peter Drucker, who coined the term “knowledge worker,” also placed productivity issues squarely in the realm of managing time:

From what I’ve observed, effective managers don’t start with tasks. They start in their own time. They don’t start with a plan. They first need to find out where their time goes.

For Drucker’s managers, work is a constant stream of tasks, interruptions, appointments, and meetings. The problem they face is trying to control the massive demands on their time, rather than the stamina required to stick to the study schedule described in the many e-mails I receive from whining students.

However, based on my own experience and decades of correspondence with readers, I feel that most of us resemble neither the simple “human machines” studied by Taylor and others, nor the captains of industry suggested by Drucker. Instead, most of us are more like the students in my inbox: we want to manage our time, but actually sticking to a schedule is much harder than planning.

I’ve encountered this problem myself. Whether it’s doing research and writing all day, or trying to stick to the pace I’ve set for myself on a project like the MIT Challenge, scheduling things isn’t hard, but actually doing the work is.

Energy is the missing key

Nearly twenty years ago, one of the first popular articles I wrote was a review of The Power of Total Engagement , an excellent book that helps explain the gap many of us feel between what we think we should be able to accomplish in the time frame we have available, and what we actually accomplish in our day-to-day jobs.

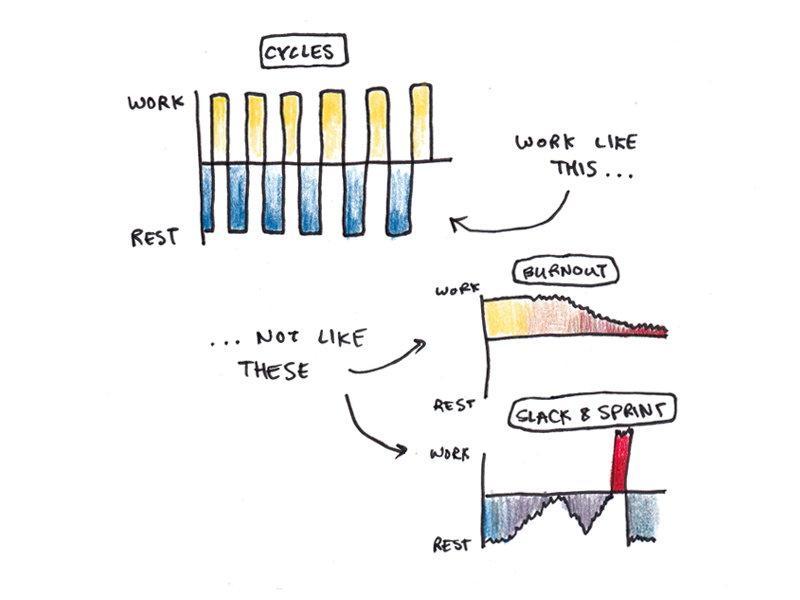

Authors Tony Schwartz and Jim Loehr argue that high-productivity work is similar to athletics, where cycles between intense exercise and recovery create training effects, and both uninterrupted work and uninterrupted rest lead to poorer results.

Schwartz and Lohr found that their typical clients were mentally overworked and physically underworked. They work long hours but get little sleep or exercise. As a result, their ability to work productively declines, and as their “theoretical” productivity goals as defined by time management slip further, they resolve to work harder to close the gap, further exacerbating their exhaustion and reducing their capabilities.

I think the prevalence of this productivity trap helps explain why so much productivity advice annoys people. When we hear “productivity,” the first thing that usually comes to mind is the push to work harder. Reflecting on our own busyness and increasing exhaustion, our subconscious mind recoils from increased stress.

But if you think about it, our most productive moments don’t actually look like this. Conversely, when we are most productive, work becomes easier. It’s easy to focus, the work is fun, and you don’t feel exhausted even if you feel tired at the end.

When your energy (not time) is managed well, work doesn’t feel so difficult. It can even be joyful.

One of the things people find strange when I retell the story of some of my reinforcement learning projects is that, by and large, they didn’t work that hard. Although studying 60+ hours a week requires concentration, most of the time I feel extremely satisfied completing these challenges.

It’s not that I’m always super productive (I’m not). I have a lot of projects that take a long time to complete, and even finishing an hour or two of work feels like pulling your fingernails out.

Productivity advice, if it’s helpful, should be a road map that explains how to make work more like those joyful projects and less like those drudgery. It should teach you how to create more situations where the work itself feels easy, even when you’re working really hard.

Energy is more than just fuel

Unfortunately, there’s no secret to easily becoming more productive. Energy itself can be a somewhat misleading metaphor. “Fuel” means that limited are some internal resources that can be deployed to any task with equal efficiency.

Rather, the ease (or lack thereof) with which we stick to the schedules and plans we create varies based on a complex set of biological and psychological factors.

These factors are what I will explore in a series of articles over the next few weeks. I’m looking at how the best existing research thinks about this question. I also share the most effective strategies I’ve found in my own experiments in the nearly two decades since I first wrote about this topic.

Now, I want to end with a thought experiment: What would you do if your job was easy? This ideal may not be completely achievable in all situations, but it at least allows us to see the gap between what we want to achieve and what we think we are capable of accomplishing. Write your answer in the comments!