What exactly is energy? -Scott H. Young

Last week, I argued that the key to productivity is energy management, not time management. Making a schedule is much easier than doing the work. Available energy is more constrained than time, which helps explain why we often fall short of our production ideals.

But what exactly is energy?

It sounds obvious: we work, we get tired, and then it’s harder to keep working. You have energy, but you run out of it. Now you are empty and work is difficult. Pretty simple, right?

Beyond that, things aren’t that simple. The science behind this “obvious” idea is extremely complex, involving biological, psychological, and sociological factors. Even a basic question, such as whether it is harder or easier to do one strenuous task after completing another strenuous task, led directly to one of the most notorious scientific controversies of the past two decades.

So today, I’m going to dive into some of those complexities. I know I have an above-average interest in esoteric social science debates, and many people are simply interested in how to feel more energized and able to get work done.

But in order to manage our energy, we first have to understand what energy is. In order to do this, we need to address this complexity.

Let’s get started. I promise it’s worth it.

Is energy a resource?

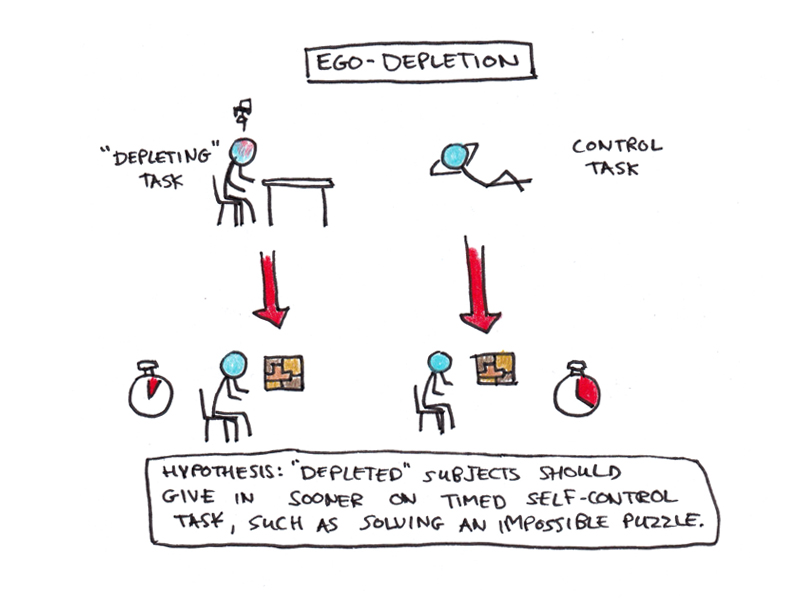

A fundamental concept of energy itself is that it is a resource of sorts: a metaphorical battery that is drained and refilled. For a while, this was the scientific consensus. In the 1990s, psychologist Roy Baumeister and his colleagues proposed the ego-depletion theory based on this premise.

Self-control, and by extension, tasks that require mental effort, draw on universal psychological “resources.” Like any good scientific theory, it makes a falsifiable prediction: People will show worse self-control after an “exhaustion” task than after a neutral control task. Energy is drained and they are more likely to give in to impulses or temptations.

Ego-depletion has an ancillary assumption: not only is energy like a battery, depleted with use and recharged through rest, but overall capacity increases or shrinks with use, like a muscle. By exercising self-control regularly, we can become more disciplined.

Both the battery and muscle analogies have a certain common-sense appeal. And, for a while, they seemed to have solid scientific backing, too. To date, more than 600 published studies in the literature have found support for ego depletion, and a 2010 meta-analysis by Martin Hagger and colleagues found that this effect was not only statistically significant but also practically significant, with effect sizes approximately 50% larger than those typically found in social psychology.

As evidence accumulated, ego-depletion researchers searched for physical properties in the brain that corresponded to behavioral effects. Many people believe they have found it: glucose.

The brain is a hungry organ. Although it only accounts for 2% of the body’s weight, it consumes nearly 20% of our daily calories. It turns out that thinking is a costly affair, and that price is paid in the form of glucose.

Once again, support is beginning not only for the behavioral reality of ego depletion, but also for its correlation with brain glucose levels. Drinking a sugary drink temporarily raised blood sugar and prevented the energy expenditure caused by mental work, but a placebo drink with added artificial sweeteners did not.

This is a textbook case of science done right: common sense observations are translated into experimental hypotheses, the hypotheses are rigorously tested in controlled experiments, and finally, the physical mechanisms mediating the effect are discovered. The end credits roll and the story ends.

Cracks in the story of ego depletion

But that’s not the case. Instead, research on ego depletion collapsed, raising questions not just about the theory but the entire social science edifice.

The first crack in the simple sugar-powered battery analogy came from an interesting experiment conducted in 2010 by growth mindset researchers Jobe, Dweck, and Walton.

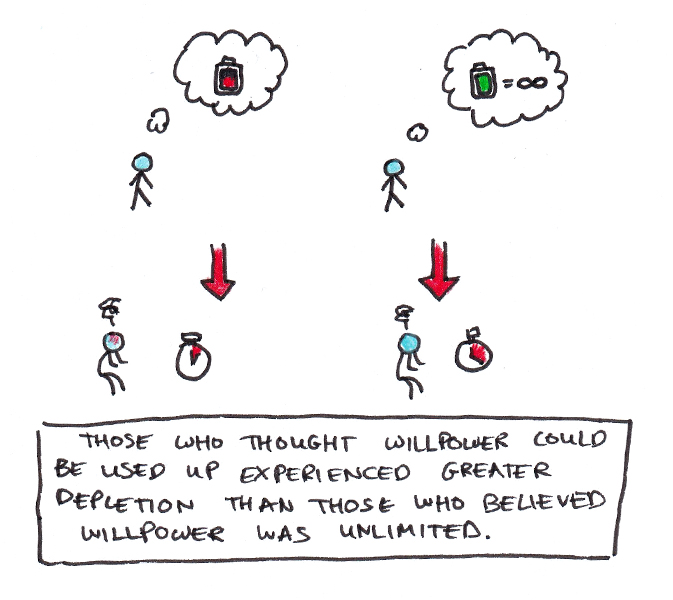

In experiments, they found that a person’s belief in willpower moderates the ego-depletion effect. If a person believes that willpower is like a drained battery, they will be more depleted on subsequent tasks than someone who believes that willpower is infinite.

But if ego depletion exploits a physical property of the brain, such as blood sugar levels, how could mere belief in willpower itself affect the outcome?

Other researchers have found that incentives may influence resource consumption. Small rewards can completely eliminate the effects of exhaustion. This is another blow to the straightforward interpretation of ego-depletion theory. After all, if your car is out of gas and stranded on the highway, throwing some cash on the dashboard isn’t going to open the secret tank.

There is an increasing attack on glucose as a biological mediator of self-depletion effects. While the brain does consume a lot of glucose, the additional amount consumed due to self-control is negligible. The visual cortex is much more taxed, but we rarely experience fatigue from simply looking at things.

Based on these findings, other researchers have proposed an alternative explanation: Perhaps ego depletion is better understood as a decline in motivation rather than a decline in resources, and thus may be influenced by beliefs or incentives. Maybe effort is a perception of opportunity cost? Or an emotional state?

Were it not for an explosive paper published in 2016, all of these attacks would have become part of the normal back-and-forth of social science, theory/counter-theory attacks that have always been made in academia.

Ego depletion and replication crisis

By this point in the story, rumors had spread that some of the psychological results were implausible. In the field of social priming, brief (sometimes subliminal) stimuli are thought to have strong effects on behavior, but difficulties have been encountered in replicating some of their classic experiments. If science is to have any meaning, it must be reliable. When different scientists conduct experiments, effects that exist on Monday do not disappear on Tuesday.

Researchers have come to realize that not publishing null results and tweaking experiments or analyzes until significant effects appear are not as innocent as they thought. To quote a team of researchers, “Everyone knows it’s wrong, but they think it’s wrong, like jaywalking. [But simulations revealed] It’s wrong, just like robbing a bank is wrong. “

After correcting for unpublished null findings, a meta-analysis of the ego-depletion effect yielded a much smaller effect size than Hagel’s original 2010 meta-analysis. Suddenly, hundreds of studies are pointing in the same direction, feeling more suspicious than confirming.

To quell doubts, Hager personally led a pre-registered replication attempt. This requires many laboratories to re-run self-depletion experiments, all following standardized protocols, making p-hacking impossible. Summary statistics published in 2016 found no statistically significant effects.

A 2016 study by a leading ego-depletion researcher failed to replicate the findings, having disastrous consequences for the field. The death of ego depletion as a theory is a cautionary tale about the dangers of imprecise science.

Ego-depletion: Returning from the dead?

Unless, of course, you know it won’t be that simple.

The ego-depletion theory has been hurt, and many early studies were fatally flawed, but it’s far from dead.

The theory was adapted in the face of several challenges. For example, new theories suggest that while ego depletion is real, we rarely find ourselves truly “empty.” Instead, we conserve energy for future use when the battery is low.

To use a new metaphor, it’s like spending money. After an expensive vacation, you may be feeling a little overspended and decide to make up for it by being more frugal with your spending in January. But that’s not to say you’re really spending your last dollar—if an emergency (or big opportunity) arises, you might find more money to spend.

Beliefs and motivations can also be viewed as inputs to our energy systems, rather than looking at things through the overly simplistic lens of a single limited resource managing all behavior.

Defenders of ego depletion argue that many failed replications fail to adequately test the theory.

First, there is a dosage issue. To coordinate the use of different tasks across many different laboratories, many large-scale pre-registered ego-depletion experiments use very short self-control tasks to “deplete” participants. The duration of these “attrition tasks” may be only 10 to 15 minutes, which may be too short to fatigue participants. Therefore, the lack of a significant effect may be due to underpowered studies rather than the effect itself being unreal.

Secondly, there is the issue of control task selection. Many experimental designs use boring tasks as “neutral” conditions. However, persisting in a boring task itself can drain our mental energy, making controlling and depleting conditions more similar than they should be.

Third, there is the question of whether the consumption tasks themselves are properly validated. Many experiments use letter-crossing tasks, in which participants are asked to read a short passage and cross out certain letters, such as “cross out any e next to a vowel.” For theoretical reasons, this type of task is thought to drain self-control. However, the researchers note that crossing out letters may be tedious, but it does not involve the types of motivational conflicts that are typical of self-control issues, such as choosing to eat broccoli or cheesecake.

Proponents argue that given these factors, ego depletion is still real, albeit weaker and more dependent on contextual factors than previously thought.

Even the fundamentals of biophysics are being revised. While the theory that glucose is a mediator of self-depletion has been completely lost, recent neuroscientific research using brainwave monitors has found elevated levels of delta wave activity (the kind typically seen in deep sleep) in areas of the brain associated with self-control after prolonged exhaustive tasks.

Perhaps, rather than burnt fuel, ego depletion is more like garbage that accumulates and needs to be collected, the metabolic byproducts of neural activity that increase the motivation for mental rest.

How well understood is 2026?

It’s clear that despite the roller coaster ride of science, consensus on energy is far from being achieved. It’s entirely reasonable to be skeptical of ego depletion, given its tainted history. I know, of course I do.

But despite my enthusiasm for promoting an early alternative theory in terms of opportunity costs, the evidence does not unequivocally support an obvious successor. Instead, and perhaps unfortunately, reality is messier than the original ego-depletion theory allows. The phenomenon of feeling burned out after working hard on something is definitely real, but the actual mechanism by which it occurs is likely a mixture of exhaustion, motivation, focus, and belief.

This chaos also has important practical consequences. This means that it’s not just a single factor like glucose that regulates how easily we do difficult things—we can’t just drink soda to boost our energy, any more than we can make a car go faster by dousing it with gasoline.

But this complexity is also an opportunity. If energy doesn’t come from a single source, but from multiple factors, we have more leverage to pull when trying to get more energy from ourselves and our work.

The story of ego depletion is a convoluted one, but it’s just one aspect of the fascinating science that keeps us feeling energized and alive. Next, I’ll move away from the controversy and discuss some more grounded science: how stress affects our health and energy levels.