The most underrated productivity tips

I’m fascinated by self-assessment: how we see ourselves versus how we actually are.

For example, when I do the first session of my foundation course, we start with fitness. I’m impressed by how many people claim to already have good exercise habits.

Now, this may be due to sampling bias in the type of readers I attract (are you really that good of a fit?). But it could also be because people in general overestimate how much exercise they actually get. In surveys, most people say they meet recommended exercise guidelines, but the reality is that less than 10 percent actually do it.

Fitness is one area where we seem to be overly optimistic about ourselves.

Now compare that to your productivity in the second month of the course. The median reaction here is not optimism, but how unproductive they are. And, since this is a paid course, many of the students are highly paid knowledge workers, among the most productive people on earth, at least by the economic definition of productivity.

Why was it disconnected? Why do we think so positively of exercise but be so hard on ourselves when it comes to work?

Productivity: tasks and priorities

I think part of this has to do with the way productivity advice as a whole is sold: most advice focuses on tackling tasks, and most people struggle more with priorities.

Task-focused advice on how to get it all done: planners, calendars, to-do lists, batch processing, Kanban boards, the Pomodoro Technique. There are countless methods designed to make you more efficient and effective in addressing the myriad desires and responsibilities we all have.

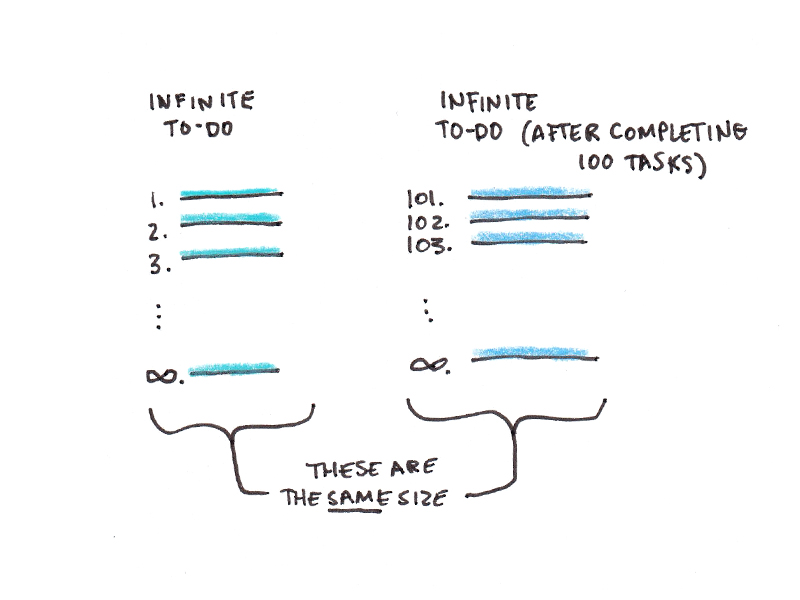

But we can’t do it all. An infinite to-do list will still contain countless things, no matter how many tasks you check off. The high-performing productivity pessimists I met on the course were judging themselves by an impossible standard.

When I recently re-read Stephen Covey’s book First Things First , this mystery came to mind: The most objectively effective people feel they are the least effective. I vaguely remember this book being about weekly reviews and his productivity system. As I remember it, it was mainly about scheduling activities each week and prioritizing important but not urgent activities.

After rereading it, I realized my memory was wrong. Much of this book actually argues against a task-focused approach to productivity in the first place. The main purpose of weekly review is not to arrange all the tasks for the week, but to ask yourself: What kind of life should I try to live?

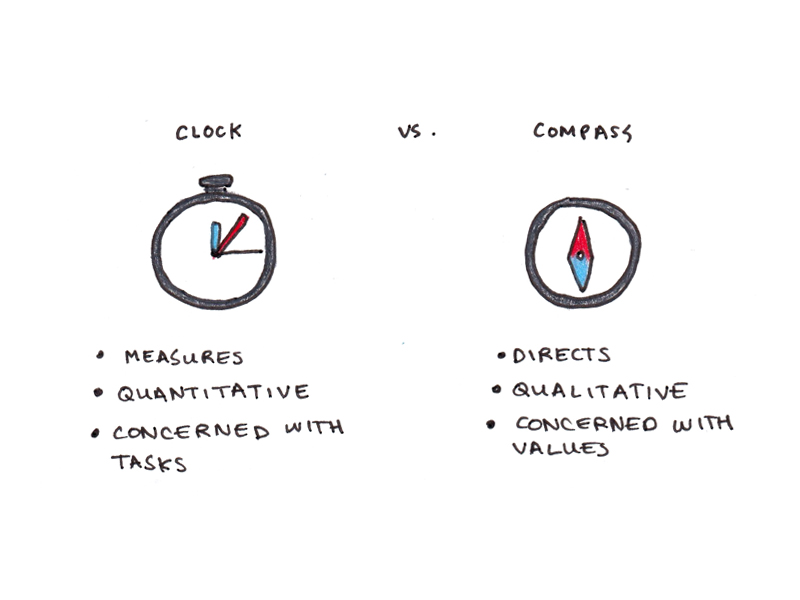

compass and clock

Of all the self-help gurus of the late 1980s, Stephen Covey is my favorite. These folk tales and aphorisms seem a bit contrived today (he didn’t even use a profanity!). But, compared to many of his contemporaries, Covey was sensible and thoughtful.

One metaphor Covey uses is comparing a clock to a compass. A clock transforms time into a measurable quantity that you can divide, allocate, and plan for—something you can manage. In contrast, a compass doesn’t give you a plan; All it can do is tell you whether you’re going in the right direction.

Ultimately, the problem with productivity is not that we don’t do everything we want to do (we never do), or that we couldn’t make better use of our time and energy (we always can). Instead, it wants to feel good about how we use the limited time we have available.

The goal of productivity shouldn’t be to worry too much about how much work we get done. Instead, we should feel at the end of the day that our time was better spent doing other things.

Ultimately, we need to develop a vision for our lives and regularly ask ourselves if we are actually achieving it. Tasks, projects, and goals will take a long time to come to fruition. Our only job is to ask ourselves what is truly important and to hold on to it.

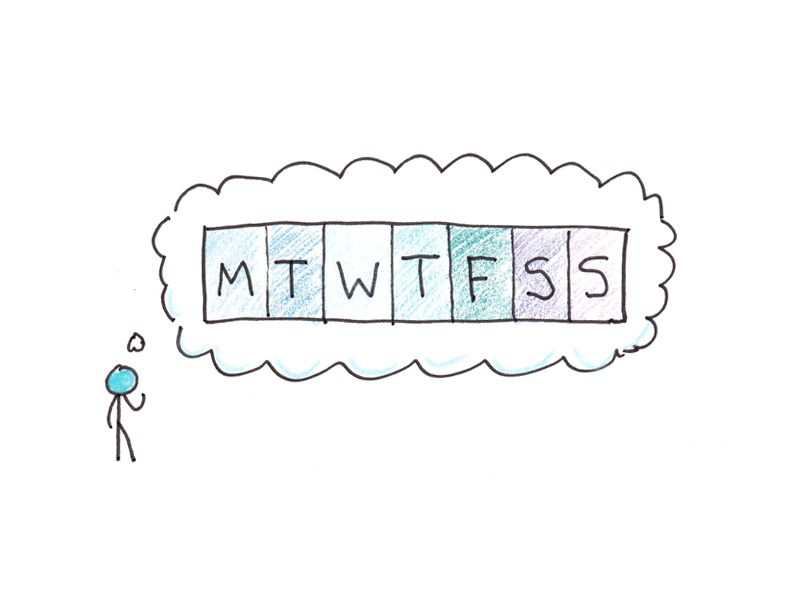

weekly review

I’ve done weekly reviews most of my life, but they were largely task-oriented: What’s on my schedule? What do I want to accomplish? What’s on your to-do list this week? What will be postponed to the future?

This part is very helpful. Life rarely goes according to plan, but the plan itself is still priceless. However, I now see that this is actually only half the method, and a less important half.

The focus of the weekly review isn’t on logistics. The purpose is not to plan out every moment of your week in advance or to determine exactly which to-do list items you need to complete. Instead, it’s an opportunity to take a few minutes to examine what’s really important to you in your life, and then make sure the week ahead is your chance to live your best life based on your answers.

Let me give you an example: If I think deeply, my children and family are more important to me than my job. My child is going through a difficult time with child care. This usually results in me taking time off or getting less work done. My first reaction in the moment is usually to blame myself for not being productive – looking at my to-do list, I’m definitely getting less done than I did when I was single and childless.

But if I take a step back, I realize it’s not a failure in productivity, it’s me becoming the most productive version of myself. At this stage of my life, I would rather do less and subordinate work to family. Weekly review reaffirmed this for me, and it changed my frustration with interruptions because I recognized that these interruptions were the real priorities in my life.

Here’s another example: I often do a lot of reading and research. Preparing for my final book was a multi-year research journey. If I compare myself to other authors, it’s obvious that my desire to delve deeper into academic research is a bit handicapped. I would probably sell more books (and write them faster) if I focused on compelling stories and sound bites instead of complex science.

But, again, taking a step back, I realized that understanding the world is one of my driving values. Spending “too much time researching” isn’t a mistake, because to me it’s more important to try to grapple with life’s complexities than to produce soothing simplifications.

Build your compass

This all sounds great, but what if you’re not sure what your values are? How do you actually make those hard decisions weighing various parts of your life and feel good about whatever consequences those choices naturally lead to?

Here I differ somewhat from Stephen Covey. He puts a lot of emphasis on personal mission statements, but I’ve always found that these mission statements are either too general and become clichés (e.g., “I will serve humanity.”) or too specific so as to unduly limit your future life (e.g., “I will serve humanity by providing excellence in quality assurance in the refrigerator repair industry.”).

Instead, I think the truth about values is that you already have them. Even if you can’t put it into words, you’ve gained a deeper awareness of what’s truly important to you in life compared to what you just feel pressured to achieve.

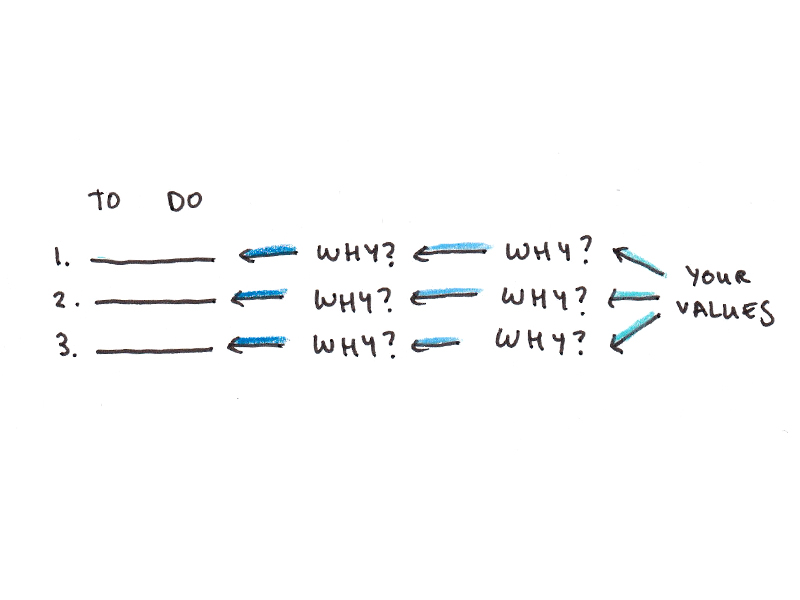

What you need is not to come up with a mission statement that you have never articulated before, but to just keep asking yourself why you do what you do until you get the answer that is self-evident.

Get a piece of paper and go through your to-do list. Start asking the “why” of each item on the agenda. Keep asking until you find a motivating reason that intrinsically appeals to you, or you realize there’s no good reason for you to do it. (In which case, cross it off your to-do list or find a way to get rid of it sooner rather than later.)

This doesn’t have to be limited to inspirational stuff. “Fix the leak in my house” may not bring joy to your life, but it’s easy to connect this task to a deeper motivation for the material well-being of your home and family. Likewise, insisting on fulfilling a onerous obligation because you agreed to do so can easily prove to be a man of his word (perhaps you will think twice before making similar commitments in the future).

What this kind of questioning does is find out which things are driving you to do them for more superficial reasons, as well as those things that really resonate with you (e.g., “I want a six-pack so people will think I’m sexy.” vs. “I want to be healthy so I can continue to live healthy into old age.”). What’s more, it can also help you recognize the things that are truly important to you but aren’t “productive” and therefore don’t typically fit into a task-oriented to-do list, such as building relationships, thinking deeply, and being kind.

Once this is done, the weekly review is an opportunity to check in on that vision each week. Not only do you have to plan when you’ll get it all done (hint: you won’t), but also make sure you spend your time doing the right things.

If you can do this, no matter how much of your to-do list gets checked off, you can end the week feeling satisfied with your productivity.